Before the TRIPS agreement, many developing countries could make cheap generic versions of life-saving drugs without breaking the law. In places like India and Brazil, local manufacturers reverse-engineered patented medicines using different production methods. A heart drug that cost $1,000 in the U.S. might sell for $50 in India. That changed in 1995, when the TRIPS agreement became law for all 164 members of the World Trade Organization. Suddenly, countries had to enforce 20-year product patents on pharmaceuticals-even if it meant people couldn’t afford their own medicines.

What the TRIPS Agreement Actually Does

The TRIPS agreement, part of the WTO’s founding rules, forces every member country to give drug companies at least 20 years of exclusive rights from the date they file a patent. That means no one else can legally make or sell the same drug during that time, even if it’s just a copy. Before TRIPS, only 23 of 102 developing countries protected drug products with patents. By 2010, that number jumped to 147. The shift wasn’t just legal-it was economic. A 2001 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that patented drug prices rose by more than 200% in developing countries after TRIPS kicked in. The agreement also banned process patents from being used as loopholes. Before TRIPS, a company in India could make the same drug using a different chemical process and still call it a generic. After TRIPS, that became illegal. The only way to legally produce a generic was to wait until the patent expired-or get special permission.Compulsory Licensing: The Legal Escape Hatch

TRIPS wasn’t completely rigid. Article 31 lets governments issue compulsory licenses-allowing local manufacturers to produce a patented drug without the company’s permission. But there’s a catch. Paragraph (f) says these licenses must be used mostly for the country’s own market. So if you’re a small African nation with no drug factories, you can’t import cheaper generics made in India, even if you have a legal license. This rule crippled public health efforts. In the early 2000s, countries like South Africa and Thailand tried to use compulsory licensing to fight HIV/AIDS. South Africa faced a lawsuit from 40 drug companies. Thailand was pressured by the U.S. government to back down. Only a handful of countries ever managed to use this tool effectively. In 2003, the WTO tried to fix this with the “Paragraph 6 Solution.” It allowed countries without manufacturing capacity to import generics made under compulsory license from another country. But the process was so complicated-requiring multiple government approvals, paperwork, and legal safeguards-that by 2016, only one shipment of malaria medicine had ever been sent this way.Data Exclusivity: The Hidden Patent Extension

Even after a patent expires, generic drugs often can’t enter the market right away. That’s because of data exclusivity, a rule not even required by TRIPS but pushed by rich countries through trade deals. It means regulatory agencies can’t use the original drug maker’s clinical trial data to approve a generic version. So even if the patent is gone, generics must wait 5 to 10 years before regulators can even review them. This is called “TRIPS Plus”-stricter rules added on top of what TRIPS requires. The EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, signed in 2020, gives 8 years of data exclusivity. The U.S. includes similar clauses in nearly all its bilateral trade deals. In low-income countries, 65% report delays in generic approval because of these extra rules. The result? A drug that should be cheap after 20 years can stay expensive for 25, 30, even 35 years. That’s not innovation-it’s legal delay.

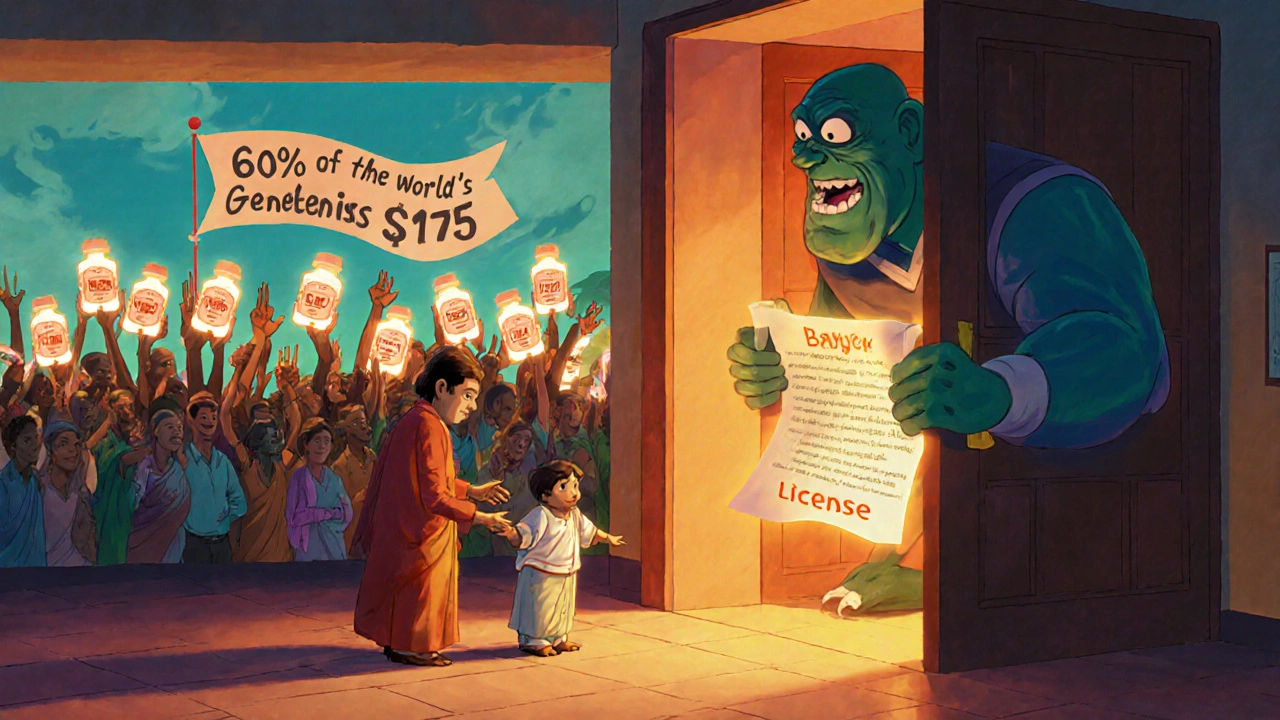

India’s Pivot: From Generic Hub to Patent Compliance

India was the world’s pharmacy. Before 2005, it didn’t grant product patents on drugs. That meant companies like Cipla and Natco could make affordable HIV, cancer, and hepatitis C medicines for the entire developing world. In 2005, India had to change its laws to meet TRIPS. The result? A 300-500% price jump for some cancer drugs, according to a 2008 Lancet Oncology study. But India didn’t give up. It kept strict patent standards. Only new chemical entities got patents-not minor modifications. That’s why, in 2012, India granted a compulsory license for a kidney cancer drug, allowing Natco to make a generic version. The drugmaker, Bayer, sued. But India’s patent office stood by its decision. The price dropped from $5,500 per month to $175. Patients across Africa and Latin America started getting the drug. India still makes 60% of all generic medicines used in the developing world. But its ability to do that is shrinking under pressure from trade deals and patent lawsuits.Real-World Impact: Who Pays the Price?

The human cost is real. In 2000, it cost $10,000 a year to treat HIV with branded drugs. By 2019, thanks to generic competition in countries that could bypass patent barriers, that cost dropped to $75. But that’s only true where governments acted. In countries that followed TRIPS strictly without flexibilities, treatment remained unaffordable. For newer drugs-like those for hepatitis C or rare cancers-the story is worse. The Access to Medicine Foundation found that 80% of medicines in low-income countries are off-patent, but still out of reach because of poor supply chains, weak regulation, or hidden patent traps. The Global Fund, UNAIDS, and Médecins Sans Frontières have all documented how patent rules delay access. One mother in Malawi couldn’t get her child the hepatitis C drug because it was still under patent. The generic version existed-but couldn’t be imported legally. She had to wait three years.

TRIPS Waiver and the Pandemic Wake-Up Call

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the world to confront the flaws in the system. In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a temporary waiver of TRIPS protections for vaccines, tests, and treatments. Over 100 countries supported it. The U.S., EU, and Switzerland blocked it for over a year. In June 2022, the WTO agreed to a limited waiver-only for vaccines, not treatments or diagnostics, and only for a few years. It was a symbolic win, but the process took 20 months. By then, millions had died. The waiver didn’t change the rules-it just gave countries a temporary excuse to ignore them. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies kept making record profits. Moderna and Pfizer earned over $100 billion combined from COVID vaccines. Yet they refused to share their formulas or license production to generic makers in Africa or Latin America.The Future: Will TRIPS Survive?

The Medicines Patent Pool, created in 2010, has negotiated voluntary licenses for 26 medicines, reaching over 17 million people. It’s a good model-but it relies on companies’ goodwill. It doesn’t change the system. Experts like Dr. Ellen ‘t Hoen and Professor Brook Baker argue that TRIPS was never meant to serve public health. It was designed to protect corporate profits. The Doha Declaration in 2001 said public health matters more than patents. But without enforcement power, it’s just words. Countries like Brazil, Thailand, and South Africa have shown it’s possible to fight back. But they’ve paid a heavy price-trade threats, diplomatic isolation, and legal battles. The next big test will come with new medicines for tuberculosis, malaria, and antimicrobial resistance. If TRIPS stays unchanged, those drugs will be priced beyond reach for billions. If the world finally reforms it, millions could live.For now, the system still works for shareholders. It doesn’t work for patients.

Does TRIPS ban all generic medicines?

No, TRIPS doesn’t ban generics. It just makes them harder to produce legally. Generic drugs can still be made after a patent expires, or through compulsory licensing if a country follows the strict rules. But many countries lack the legal tools, manufacturing capacity, or political will to use those options.

Why can’t poor countries just import cheap generics from India?

Before 2007, they couldn’t. TRIPS required compulsory licenses to be used only for domestic supply. Even if India made a generic under license, exporting it to another country was illegal. The 2007 amendment fixed this-but the process is so complex (needing approval from both exporting and importing countries, plus detailed paperwork) that only one shipment of medicine has ever been sent this way. Most countries just give up.

What’s the difference between a patent and data exclusivity?

A patent gives the drugmaker exclusive rights to make and sell the drug for 20 years. Data exclusivity is different-it prevents regulators from using the original company’s clinical trial data to approve a generic, even after the patent expires. That adds 5-10 more years of monopoly. Data exclusivity isn’t required by TRIPS, but rich countries force it into trade deals.

Did the TRIPS waiver for COVID vaccines make a difference?

Not really. The waiver only applied to vaccines, not treatments or diagnostics. It was temporary and didn’t force companies to share technology or know-how. By the time it passed, most high-income countries had already hoarded doses. Low-income countries still couldn’t produce vaccines locally because they lacked the factories, equipment, and expertise-not just the legal right.

Is India still a source for affordable generics?

Yes-but less than before. India still produces 60% of the world’s generic medicines. It still rejects patents on minor drug changes. But after 2005, it had to start granting product patents. Now, companies can sue if generics are made too soon. Some Indian manufacturers still produce low-cost drugs for Africa and Latin America, but they face more legal risks and pressure from Western governments.

What can countries do to protect access to medicines under TRIPS?

They can use TRIPS flexibilities: compulsory licensing, parallel importing, and strict patent standards (like only patenting truly new drugs, not minor tweaks). They can also refuse to adopt TRIPS Plus rules in trade deals. But they need strong legal teams, political courage, and international support. Countries that try-like Thailand, Brazil, and South Africa-often face trade threats or lawsuits. Still, it’s possible.

Are there any alternatives to TRIPS for global drug access?

Yes. The Medicines Patent Pool lets manufacturers license patents voluntarily. The WHO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool tried to do the same for pandemic tools. Some experts propose a global fund to pay for R&D without patents, so drugs are treated as public goods. But these are voluntary, not binding. Without replacing TRIPS, they’re temporary fixes, not solutions.

Nikki C

November 23, 2025 AT 22:58They turned medicine into a luxury item and called it progress

People die because a corporation owns the formula for a drug that keeps them alive

It’s not capitalism-it’s cruelty dressed up as law

Neoma Geoghegan

November 25, 2025 AT 09:19TRIPS was never about innovation-it was about market control

Pharma’s lobbying power > public health any day

India still fights the good fight though

Alex Dubrovin

November 25, 2025 AT 21:30so like… if i’m in a country that can’t make generics and can’t import them… i just wait to die?

that’s the system

stephanie Hill

November 26, 2025 AT 08:56the real horror story? they knew this would happen

they planned it

the same people who profit from your suffering also write the laws

and they laugh while you choke on the price tag

Jacob McConaghy

November 28, 2025 AT 07:37India’s patent office standing up to Bayer in 2012? that’s the moment the system cracked

It’s not perfect but it’s proof you can push back

And that’s why they’re coming for India harder now

They don’t want the example to spread

Bartholemy Tuite

November 29, 2025 AT 10:08let’s be real here-TRIPS wasn’t some neutral trade deal

it was a power play wrapped in legalese

rich countries said ‘you want to export textiles? fine-but you also have to let us lock down your medicine supply’

it’s economic colonialism with a WTO stamp

and the ‘flexibilities’? those are like giving someone a key to a locked room… then hiding the key under a rug

and telling them to find it before they die of thirst

the paragraph 6 solution? a bureaucratic nightmare designed to fail

only one shipment in 13 years? that’s not a loophole-it’s a joke

and data exclusivity? that’s the sneaky second patent

patent expires? cool

but you can’t even *review* the generic for another 8 years

so the drug stays at $5000/month while the company files another patent on the color of the pill

it’s not innovation-it’s legal extortion

and the worst part? most people don’t even know this is happening

they think the drug’s expensive because it’s ‘hard to make’

no-it’s expensive because someone decided it should be

akhilesh jha

December 1, 2025 AT 02:18India made life-saving drugs for the world

Now we are told to bow to patents

But the people still remember

And the generics still find a way

Even if the law says no

The heart says yes

Douglas cardoza

December 2, 2025 AT 14:49so the waiver for covid vaccines took 20 months

and only covered vaccines

and didn’t make companies share tech

and by then the rich countries had already bought up all the doses

so basically the whole world watched as people died

and the answer was ‘uhhh we’ll try’

and then they gave out a medal for trying

bravo

Natashia Luu

December 4, 2025 AT 03:21It is unconscionable that the global intellectual property regime prioritizes shareholder dividends over human life.

This is not a matter of policy-it is a moral catastrophe.

The commodification of essential medicines represents a fundamental betrayal of the social contract.

It is a systemic failure of unprecedented ethical gravity.

Every delay in generic access is a death sentence written in legalese.

There are no neutral actors here.

There are only perpetrators and the dying.

And the perpetrators wear suits.

They attend conferences.

They give speeches about innovation.

They donate to universities.

They call themselves philanthropists.

They are not heroes.

They are not innovators.

They are profiteers.

And history will judge them with the same contempt as the slave traders.

There is no excuse.

There is no justification.

There is only guilt.

Yvonne Franklin

December 5, 2025 AT 21:55compulsory licensing works if you have the guts to use it

Thailand did it for HIV

Brazil did it for antivirals

India did it for cancer drugs

the problem isn’t the law

it’s the fear of being sued

or having your exports blocked

or your aid cut

you need political will

and you need to not care what the U.S. thinks

Sam Jepsen

December 6, 2025 AT 13:45the Medicines Patent Pool is the quiet hero here

not flashy

not in the headlines

but it got 26 drugs to 17 million people

by getting pharma to *voluntarily* share

which proves one thing

they can share

they just choose not to

until someone makes it easier

or cheaper

or more profitable to do the right thing

Vineeta Puri

December 6, 2025 AT 15:13TRIPS was negotiated without the participation of the most affected populations.

It was designed by legal teams, not public health experts.

It reflects the interests of capital, not human dignity.

Reform is not optional.

It is a moral imperative.

Every life lost to preventable disease under this system is a failure of global governance.

We must demand structural change, not temporary waivers.

Patents on medicine are incompatible with the right to health.

Let us not mistake compromise for justice.

Andy Louis-Charles

December 8, 2025 AT 04:28just saying… if you can patent a pill

but not the idea of saving lives

then maybe the system is broken 🤷♂️💊

Victoria Stanley

December 9, 2025 AT 23:14the real win isn’t the waiver

it’s that 100+ countries stood up and said ‘enough’

even if the U.S. and EU blocked it

they showed the world this isn’t normal

and that’s how change starts

not with a law

but with a chorus of ‘no’

Jeff Hicken

December 11, 2025 AT 19:35so like… the whole system is just a giant scam?

patents = monopoly

data exclusivity = more monopoly

trade deals = even more monopoly

and the waiver? a bandaid on a bullet wound

and we’re supposed to be impressed?

bruh