Ever wonder why some pills have long, confusing names like omeprazole while others are called Prilosec? Or why your doctor says metformin but the bottle says Glucophage? It’s not random. There’s a whole system behind how drugs get their names-and it’s designed to keep you safe.

Why Drug Names Even Matter

Medication errors kill over 250,000 people a year in the U.S. alone. A big part of that? Confusing drug names. Two drugs that sound alike or look alike can get mixed up in a hospital, pharmacy, or even at home. That’s why scientists and regulators spent decades building a global naming system that tells you what a drug does just by its name.

It’s not about marketing. It’s about clarity. A well-chosen name can prevent a nurse from giving you the wrong medicine. It can help a pharmacist spot a dangerous interaction. And it lets doctors across the world communicate clearly-even if they speak different languages.

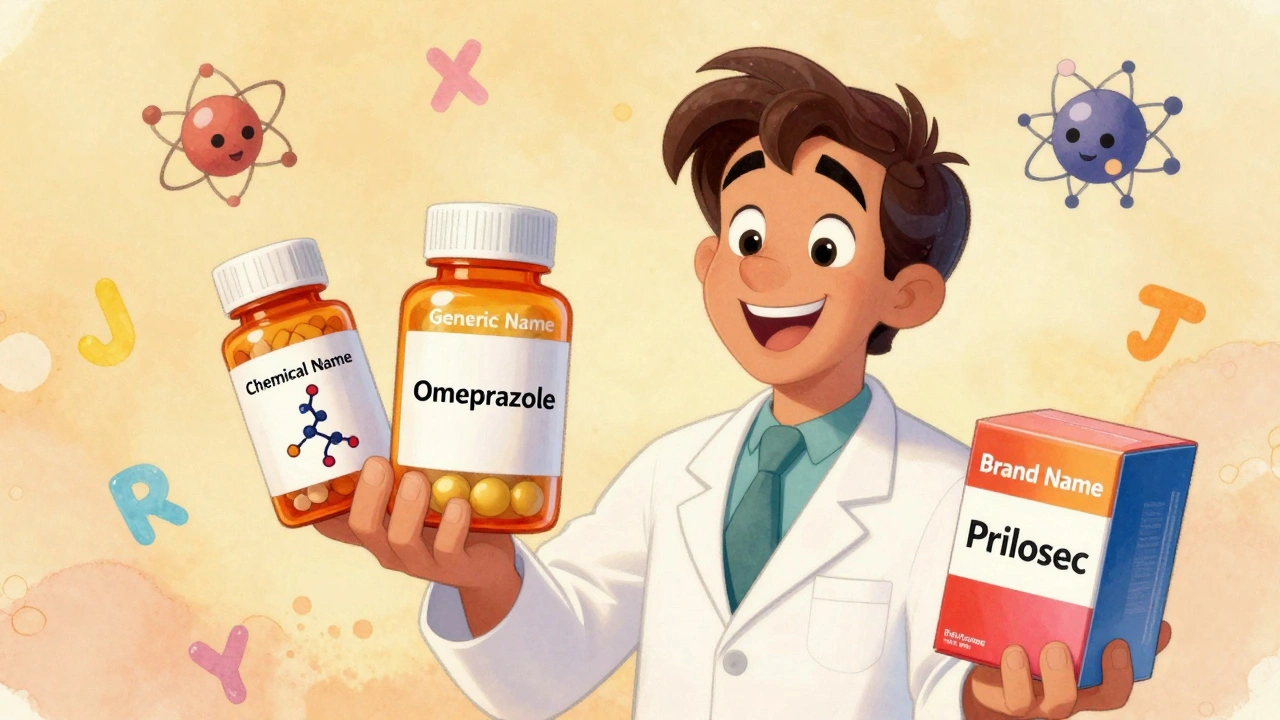

The Three Layers of a Drug’s Identity

Every drug has three names. Think of them like a person’s legal name, nickname, and stage name.

- Chemical name: The scientific blueprint. Long, precise, and unreadable to most people.

- Generic name: The official medical name. Used by doctors, pharmacists, and regulators.

- Brand name: The commercial label. What you see on the box and in ads.

Only one of these is required on every prescription. The generic name. And here’s why.

Chemical Names: The Molecular Blueprint

Chemical names follow rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). They describe the exact structure of the molecule-atom by atom, bond by bond.

Take propranolol. Its chemical name is: 1-(isopropylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy)propan-2-ol.

That’s 51 characters. Try saying that out loud during an emergency. Good luck.

Chemical names are useful only in labs. They’re too long, too technical, and too hard to remember. No pharmacist writes this on a label. No doctor says it to a patient. But they’re the foundation. Every generic and brand name starts here.

Generic Names: The Safety Code

Generic names are where safety really kicks in. They’re not random. They’re built like a code.

Since the 1950s, the World Health Organization (WHO) has run the International Nonproprietary Names (INN) program. The U.S. has its own version, called United States Adopted Names (USAN), created in 1961. Together, they’ve assigned over 10,000 names.

Here’s how they work:

- Stem: The ending tells you the drug’s class. -prazole means it’s a proton pump inhibitor (omeprazole, pantoprazole). -tinib means it’s a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (imatinib, sunitinib). -mab means it’s a monoclonal antibody (adalimumab, rituximab).

- Prefix: The first part makes it unique. Om-prazole, La-nospazol, Pan-toprazole. These are chosen to avoid sounding like other drugs.

That’s why you’ll see atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin all ending in -statin. They’re all cholesterol-lowering drugs. The stem tells you that instantly.

But it’s not just about class. The USAN Council rejects about 30% of proposed generic names because they sound too similar to existing ones. One rejected name? Fluoxetine was almost called Fluoxetin. Close enough to confuse with Fluoxetine? Yes. Rejected? Yes.

Dr. Robert Goggin, former head of USAN, says standardized naming cuts medication errors by 27%. That’s not a guess. It’s backed by data from hospitals.

Brand Names: The Marketing Mask

Brand names are what drug companies spend millions on. They’re catchy. They’re memorable. And they’re tightly controlled.

Before a company can sell a drug under a brand name, they submit 150-200 options to the FDA. The FDA’s team checks each one for:

- Similarity to existing drug names (spelling, sound, appearance)

- Hidden claims (like “CureAll” or “PainFree”)

- Confusion risk across languages and scripts

One in three brand names get rejected. In 2022, the FDA blocked a name that looked too much like Hydralazine. Another was turned down because it sounded like Prozac when spoken quickly.

Companies also use internal codes during development. Pfizer uses PF-04965842-01 for what later became abrocitinib. The first two letters are the company code. The numbers track the compound and salt form. It’s like a barcode for molecules.

And here’s the twist: brand and generic drugs contain the exact same active ingredient. Same dose. Same way it works. But they look different. Different color. Different shape. Different flavor. Why? Because trademark law says they can’t look identical. That’s why you might get a blue oval one day and a white capsule the next. Same medicine. Different packaging.

But that difference caused 347 medication errors in 2022 alone, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Patients thought they got the wrong drug because it looked different.

How the Naming Process Actually Works

It’s not a quick process. It takes years.

- Discovery: A compound is made in a lab. It gets a company code (like PF-04965842).

- Phase I Trials: Around 2-3 years in, scientists start picking a generic name. They work with USAN or WHO to find a name that fits the stem rules and avoids confusion.

- Phase III Trials: The brand name team starts testing names. Focus groups. Linguistic checks. Computer simulations that scan 15,000 existing drug names for similarities.

- Approval: The FDA approves the brand name about 6-12 months before launch. The generic name is already locked in.

From molecule to market? Four to seven years. And naming is one of the first things they lock in.

What’s Changing Now

Drugs are getting more complex. We’re not just making pills anymore. We have RNA therapies, peptide-drug conjugates, targeted protein degraders.

So the naming system is updating.

- RNA-based drugs now get the stem -siran (e.g., vutrisiran).

- Peptide-drug conjugates use -dutide.

- Targeted protein degraders are getting -tecan (like ARV-471, though it’s still early).

The USAN Council now uses AI to screen names in milliseconds. In 2022, that system cut confusion risks by 42%.

By 2030, experts predict stem-based naming will grow by 300% as new drug types explode onto the market.

What You Need to Know as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize stems. But you should know this:

- Generic drugs are just as safe and effective as brand-name ones. The FDA requires them to be identical in active ingredients.

- Brand names change. Generic names don’t. If you switch pharmacies and your pill looks different, it’s probably the same generic drug.

- If a name sounds weird or hard to pronounce, you’re not alone. The average generic name is 12.7 characters long. But that’s intentional-it’s designed to be unique, not easy.

- Always check the active ingredient on the label. That’s what matters. Not the brand.

And if you’re confused? Ask your pharmacist. 83% of pharmacists say standardized names make their job safer. But 68% of patients say they don’t understand the names without help.

Knowledge is your best defense. Know your drug’s generic name. Write it down. Use it when you refill. That’s how you avoid mix-ups.

Why This System Works-And Why It’s Necessary

Global health systems serve over 7.9 billion people. Without a shared naming system, we’d be lost. A drug called Alprazolam in the U.S. is Alprazolam in Brazil, India, and Germany. That’s because of INN.

Since 2010, standardized naming has cut international medication errors by 18.5%. That’s thousands of lives saved.

It’s not glamorous. No one writes songs about lisinopril. But it’s one of the quietest, most effective safety nets in modern medicine.

Next time you pick up a prescription, look at the generic name. See the stem. It’s not just a label. It’s a warning system. A code. A promise that someone, somewhere, spent years making sure you wouldn’t get the wrong pill.

Why do generic drugs have such strange names?

Generic names aren’t random-they follow strict international rules. The ending (stem) tells you what type of drug it is, like -prazole for acid reducers or -tinib for cancer drugs. The beginning makes it unique. These names are designed to avoid confusion with other drugs, not to sound nice. That’s why they’re long and technical. It’s a safety feature.

Are brand-name drugs better than generics?

No. By law, generic drugs must contain the exact same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. The only differences are in inactive ingredients-like color, shape, or flavor-which are changed to avoid trademark conflicts. Both work the same way in your body. The FDA requires generics to be just as safe and effective.

Can two drugs with similar names be dangerous?

Yes. Drugs like Hydralazine and Hydroxyzine sound alike but do very different things-one lowers blood pressure, the other treats allergies. Mistaking one for the other can be deadly. That’s why the FDA rejects up to one-third of proposed brand names for sounding too similar to existing ones. Pharmacists and doctors rely on clear naming to prevent these mix-ups.

Why do some drugs have different names in different countries?

Brand names often change by country because of trademark laws and marketing. But the generic name stays the same worldwide thanks to the WHO’s International Nonproprietary Names (INN) program. So whether you’re in Tokyo or Toronto, metformin is always metformin. That’s why doctors use generic names when writing prescriptions.

How do I know if I’m getting the right drug?

Always check the active ingredient on the label. That’s the generic name. It’s listed right under the brand name. For example, if you’re taking Advil, the active ingredient is ibuprofen. If you switch brands or pharmacies, the shape or color might change-but the generic name should stay the same. If it doesn’t, ask your pharmacist.

amit kuamr

December 1, 2025 AT 18:55Generic names are just a mess honestly. Why do they have to be so long? I get it's for safety but come on, -prazole? -tinib? Sounds like a spell from Harry Potter. My grandma can't even say them right.

elizabeth muzichuk

December 1, 2025 AT 19:02People don't realize how dangerous this is. The FDA lets companies sneak in names that sound like other drugs just to make them stick in people's heads. It's not about safety-it's about profit. And now they're using AI to make it worse? This is corporate greed disguised as science.

Debbie Naquin

December 2, 2025 AT 15:09The stem-based nomenclature is a brilliant example of semiotic efficiency in pharmacological systems. By encoding pharmacodynamic class into morphological structure, the INN/USAN framework reduces cognitive load during high-stakes clinical decision-making. The -mab suffix, for instance, immediately signals monoclonal antibody origin, enabling rapid cross-referencing of mechanism-of-action profiles across heterogeneous provider populations. This is linguistic engineering at its most functional.

Karandeep Singh

December 4, 2025 AT 10:20generic drugs r the same as brand but cheaper so why do we even have brands? pharma companies are just ripping us off

Mary Ngo

December 6, 2025 AT 02:00Have you ever considered that this whole naming system might be a controlled distraction? The FDA, WHO, and Big Pharma are all part of the same globalist agenda. They want you confused so you don’t ask why your insulin costs $300. The real story? They’re hiding the truth about drug efficacy. The stems? Just a placebo for trust.

James Allen

December 7, 2025 AT 04:01Look, I get that naming is important, but let’s be real-this is all just fancy talk to make Americans feel better about paying more. Other countries just use the generic name and move on. We’re the ones who need a brand name to feel like we’re getting something premium. It’s pathetic.

Kenny Leow

December 8, 2025 AT 08:50Really appreciate this breakdown. As someone who’s worked in healthcare across 5 countries, the consistency of generic names is the only thing keeping me sane. 👍

Kelly Essenpreis

December 9, 2025 AT 12:09Why do we even care about this? People don’t read labels anyway. They just take whatever the pharmacist hands them. This whole system is just theater. Save the money and let people pick whatever looks nice

Alexander Williams

December 10, 2025 AT 19:20Stem-based nomenclature is a taxonomic artifact of 20th-century pharmacology. It’s inefficient for polypharmacological agents and fails to account for pleiotropic mechanisms. The -tecan suffix for protein degraders? Arbitrary. We need a semantic ontology, not linguistic conventions.

Suzanne Mollaneda Padin

December 11, 2025 AT 09:29Just wanted to add-when I worked at a community pharmacy, patients would come in panicked because their pill changed color. Once we explained the generic name was the same, they relaxed. It’s not about branding. It’s about education. Talk to your patients. They’ll thank you.

Erin Nemo

December 11, 2025 AT 16:54So basically the generic name is like your legal name and brand name is your Instagram handle? That actually makes sense now.

ariel nicholas

December 12, 2025 AT 16:02Wait… so the FDA rejects names because they’re “too similar”? But they approve drugs that cause 250,000 deaths a year? That’s not safety-that’s hypocrisy. They’re more worried about trademark confusion than actual patient harm. This system is broken. And it’s all part of the plan.